By Ilana Stein – Did you know that extinct species can be brought back to life through a process called de extinction? We could create a world that we share with the great woolly mammoths!

Defining and Explaining De Extinction

De extinction is defined as: “the process of resurrecting species that have died out, or gone extinct.” Today, thanks to huge leaps in technology, it seems that we have the ability to use an extinct genome to resurrect extinct species and bring them back to life. This process is also known as resurrection biology.

Bringing Extinct Animals Back to Life

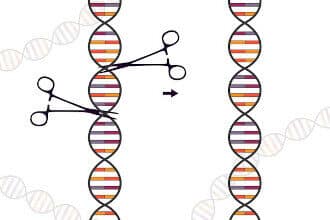

De extinction techniques are incredibly complex experiments in molecular biology. The first step is to find the most closely-related species, known as a candidate species – or locate a species that is genetically identical to the extinct species.

Sometimes museum specimens can be used to obtain the germ cells needed. If the animal is an extinct subspecies, DNA can be taken from an existing subspecies.

Then, with genetic engineering or genome editing, the genome or ‘germ-line’ of the living species is ‘edited’ to resemble that of the extinct species, after which ‘back breeding’ is done. If this all succeeds, then it may be possible to reintroduce the resurrected animals into their former habitats.

What is important to note is that often, the species being brought back is not the original species, but something that is close enough in its DNA. De extinction is very much still in the development phase, but that development is moving rapidly.

Can All Species Be Brought Back to Life?

That depends on the DNA or germ cells. The primordial germ cells of dinosaurs, for example, are too old and degraded to reanimate (and many, with Jurassic Park in mind, are thankful for this!).

The Revive and Restore Project

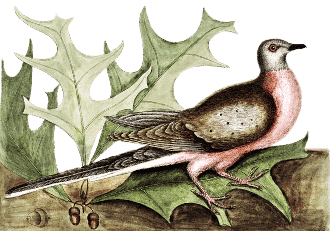

There are a number of de extinction programs currently operating. One such program, “The Revive & Restore Project”, is looking to resurrect the extinct passenger pigeon.

Passenger pigeons are one of the most famous species in the world to become extinct. Once found in the millions across North America, due to hunting and habitat loss, the passenger pigeon became extinct, the last one dying in Cincinnati Zoo in 1914.

The project discovered that the closest living species to the passenger pigeon is the band-tailed pigeon so genetic technologies are being used to edit their germ cells and identify key genes. These are used in selective breeding techniques so as to breed back to the first species.

Other species to de extinct

A famous project is looking at bringing back to life the woolly mammoth. A less well known project is the attempt at de extinction of the heath hen, “an extinct subspecies of the greater prairie chicken” which lived in huge numbers in New England. The heath hen became extinct by 1932, primarily due to hunting. It is also the first species that US conservationists attempted to bring back from the brink, but to no avail.

It’s not just about one lost species

This is not only about seeing passenger pigeons taking to the skies, or heath hens running around the prairies. The study of nature ecology has resulted in the realization that it is not just the extinct organism that counts but the gap it leaves in the ecosystem.

For example, the woodland biodiversity of the eastern United States would benefit from the passenger pigeon as a resurrected species. So bringing back passenger pigeons, or the heath hen, may well improve the overall health of biodiversity in North America, thus making it an important conservation tool.

Another animal is the extinct wild ox or aurochs of Europe. It is understood today that the European landscape was a mixture of forest and grassland, and that the aurochs helped to keep it that way. If the extinct wild ox were resurrected, it could help us “rewild” European countries.

To De Extinct Or Not To De Extinct?

Should we resurrect extinct animals? The jury is out, both from the point of view of which animals to bring back and whether to do so at all.

An example of this is the Christmas Island rat – also known as Maclear’s rat. It is a large rat endemic to Christmas Island, in the Indian Ocean, whose numbers were decimated when the black rat was inadvertently brought onto the island in the 1800s. The Christmas Island rat succumbed to a disease carried by the invasive black rat species. The last individual Christmas Island rat died in 1903.

Recently, researchers have been working on bringing this species back. Using gene-splicing technology, great strides have been made, but not all of the Christmas Island rat genome was recoverable, which means that from a scientific point of view we do not know what part of the rat’s existence will have changed – or even, what will have been created?

The Ethics of De Extinction

Clearly, it is the ethics of the project that bother many people. It is all very well to bring a species back to life, but if the only place the resurrected animals can live is a zoo, then the species remains functionally extinct, and many in the biological sciences oppose this vehemently.

If they are released, then why achieve the genetic rescue of a species only to have it struggle to live in a former habitat, one that is no longer viable thanks to human action? If the result of de extinction is to put creatures in zoos, it seems like a highly unethical move.

Conservation OR De Extinction?

While the idea of bringing some of the species back to life that humankind has destroyed or that became extinct on their own is extremely tempting, many scientists are of the opinion that our conservation efforts and conservation funding should rather go to endangered species today which are disappearing rapidly – again thanks to human action.

Having said this, even if bringing an extinct species back seems more exciting than protecting an endangered species, scientists note that: “The same techniques being developed to help resurrect extinct species can also be used to help save living species on the brink of extinction.”

Religion and De Extinction

From a religious point of view, are we allowed to re-create animals? There are many different views on the matter.

Reverend Donna Schaper discusses the downside of de extinction on EarthBeat. She shares her deep concern that by the de extinction of species we threaten the natural order:

We can love things and we can lose them. When we hang on too tight to any species, or beloved, or moment in time, we move out of the great flow of infinity, which is God’s name for time and space.

Once we are part of the great ongoing conversation that Charles Darwin called evolution, once our genes are in the mix, we flow on. Flowing on is so much better than fixing. I’m not “against” de-extinction science. Instead, I am for going with the flow of God’s life and death pattern for infinity.

In other words, de extinction is a rebellion against God’s ordering of the world. Creatures live and die. And that’s the way it should be.

Dr. Rolf Bouma offers another perspective on de extinction, expressing uncertainty about how God feels about de extinction, but offers the following supposition: “my instincts tell me that if we champion God as the author of life, then God is more pleased by de extinction than by extinction.” If God is all about life, the more we can do to create life, the better. But on the other side of this issue is what kind of life are we creating and what will the lives of these creatures be like?

Dr. Bouma is concerned about cloning creatures that will all have the same genetics, making for a very unhealthy species. He’s also concerned about bringing back extinct species without them having the appropriate habitat. His last argument implies that if scientists undergo de extinction of creatures that are disappearing because their habitat is being destroyed, then we may be less motivated to protect that species and their habitat. If we can just bring it back to life later, than we lose the impetus to protect that species and their home in the here and now.

A Balancing Act

Most people believe that we should prioritize saving the species that are disappearing every year at an alarming rate over investing millions of dollars in the de extinction of animals. We have limited resources, so the question is how to channel them?

Bringing back extinct species may be an interesting way to flex our technological prowess, but the more pressing need is to protect the species and habitats that we’re wiping out— before it’s too late for all of us.

* Featured image source