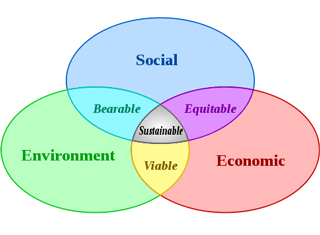

By Matthew Mausner – An old maxim about business says that you can have any two of the following three principles: Good, Fast, and Cheap. Pick two. For a sustainable future, the challenge is that we need all three– despite knowing that they all involve tradeoffs and potentially pull in different directions. Economic, Social, and Environmental spheres all can be ‘optimized’ or prioritized in different ways, as you see in the diagram above. The Bible reminds us, “a cord of three strands is not quickly broken,” (Ecclesiastes 4:12). Similarly, it is only when all three pillars of sustainability are achieved that human civilization can be said to be genuinely sustainable.

This is the Venn diagram of sustainable development. Making these principles fit and work symbiotically is the essence of sustainable development. Sustainable development is the assurance that the integrity of the present needs can be met without compromising resources in the future. The United Nations definition of sustainable development is “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

A Pillar Can Not Stand Alone

In a sense, ‘sustainability’ is precisely the best measure of the success of the others. For example, if economic needs are given too much focus over the environment, it can cause a collapse of the environment, with the cascading collapse of that part of the economy, such as overfishing or deforestation. The over-use of the environment’s natural resources directly impacts humanity’s well-being.

Weakness of The Environmental Pillar Alone

If the environment is pursued to the exclusion of the economic or social, such as protection of big game in Africa in the 1980s, it can lead to a backlash of activity, as desperate and starving Africans legally excluded from land use in the region took to newly lucrative poaching in order to ensure their basic human right to survive, and it undermined the environment that the rules had been designed to protect.

Of the three pillars of sustainability, the environment and the depletion of natural resources for future generations pose a giant threat. The environmental pillar includes environmental protection and securing the ecological needs of our green systems of the world.

Weakness of The Social Pillar Alone

If the social is pursued to the detriment of the others, similar consequences follow. A high standard of living, strong community life, and thriving economy that is built on exploiting other countries’ natural resources far away will lead to environmental degradation, pollution, and migration that eventually undermines the social and economic fabric of even the richest countries.

The concept of the three pillars helps us identify where they all overlap, and therefore which priorities to balance. And only when all three are honored, with all the detailed implications, we can approach sustainability. We can call that a triple bottom line.

How The Three Pillars Can Work Together

Sometimes looking at the short-term and the long-term framework can also help clarify what is genuinely sustainable. Durability and stability are harder than they look, as even a system or practice that works efficiently for 5 or 10 or even 30 years runs increasing risks of breaking down.

Socially there are risks over time of even a well-run industry or government becoming stagnant or corrupt or top-heavy, leading to declines in economic performance. Economically optimizing might lean towards efficiency- and inequality, as natural ‘hockey stick’ and monopoly trends emerge, that damage the social system.

The Pillars and the Fragility of the Natural World

And the natural world, with its cycles of nutrients and seasons and interdependency of species for pollination and shade and fertilizer and more, is inherently fragile in the face of a consistently exploitative human practice of agriculture, animal husbandry, fishing, or other resource use. Even a reasonable ‘crop rotation’ might exhaust soils eventually, and limits on fishing, when not rigorous enough, can reduce a population below replacement over time.

Balance and Sustainability: A Basketball Example

So how do you make decisions that even address, much less genuinely optimize and balance all three pillars of sustainablity? I can give the analogy of a sports team striving for sustainable success, like the San Antonio Spurs. They must strive for as many wins as possible each season, like ‘economic’ growth and success (which it does in fact translate into).

They attempt to preserve their players’ health, managing their minutes and resting them as needed, like ‘environmental’ sustainability. And yet they must stay sportsmanlike- not compete unfairly- and when there are nationally televised games, they are expected to play their best lineups (like ‘social’ sustainability, for the good of the league as a whole).

Sustainable Spurs

This became an issue many people noticed when the Spurs became the first team to rest their star players in the second game of ‘back-to-back,’ two-nights-in-a-row games, despite it being nationally televised. They were fined for that, and their often quotable coach in response described exactly the three-pronged logic. It’s always a balance, and even this most-successful-franchise was having trouble balancing the development of all three pillars of sustainability.

A Shared Vision of the Three Pillars

The Spurs have the advantage of ownership, management, coach, and training staff that are all on the same page about how to achieve all three goals. Many other teams sacrifice the long term for the short term, or the short for the long (‘tanking’), or take risks with players’ health (some risk is inevitable in a contact sport, but some teams used to be accused of inadequate rehabilitation or other physical management issues.)

The Three Pillars and the Tragedy of the Commons

Ecological economics speaks about the “tragedy of the commons,” a situation in a shared-resource system where individuals act independently, according to their own self-interest. In so doing, they behave contrary to the common good by depleting or spoiling a resource through their collective actions. The classic, historical example is of many shepherds grazing sheep on a collective field (the commons).

Each shepherd tries to maximize his or her grazing of sheep, even though overgrazing is ultimately to the long-term detriment of all. Professor Elinor Ostrom of Indiana University was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics for characterizing the ways that cooperative agreements allow communities to break out of the “tragedy of the commons” dynamic. A group of sheep owners sharing one field for grazing might agree collectively that it would be sensible to leave the field fallow for a period of time in order to regrow its grass.

If everyone could be trusted to cooperate, it would be in their combined best interests to leave enough grass to regrow (or in the case of fishing, enough fish to breed). But in the absence of cooperation, many individuals will consume the complete stock of grass or fish. In this situation, their long-term best interests are achieved only when each person acts against their own short-term self-interest.

Politics of Sustainability

But in our society, decision-making and political power is distributed, some might say balkanized. Those who advocate for any one goal are pulling very hard in that one direction, otherwise, it will probably be sacrificed to the other two pillars of sustainability.

Entire political parties sometimes pull towards the environmental impact on future generations, like the green party in several European countries. Others insist on the primacy of the economy, such as many right-leaning or conservative parties in most Western countries. And some prioritize the social safety net, protections for workers, and regulating the profit-driven actions of the economic and corporate actors of their countries.

Since the political process is in effect adversarial, with extremes driving voter turnout and each side often forced to compromise in order to work together, very little incentive exists for a true balancing of economic, environmental, and social goals.

The Pillars and the Spurs

All the more so when short-term election motives leave little room for long-term planning. The San Antonio Spurs made the playoffs over 20 years in a row and won 5 NBA championships; such sustained success is rare or absent in democratic politics.

But the consequences of failure are worse for nations. If the Spurs stop winning so many games, their fans may be patient or forgive them, or they may not; but if countries fail to balance the social, economic, or environmental bottom lines, they face outright civilizational collapse.

An Un-Sustainable Example

An example is the sad story of the Aral Sea. As recently as the 1980s it was the world’s fourth-biggest lake, in the central Asian region of the former USSR. Well-intentioned officials and engineers wanted to encourage agriculture along the Syr Darya and Amu Darya rivers in this relatively impoverished area and irrigated 2.5 million acres of farmland in an attempt to improve both the economic and social situation.

At first, it looked like it succeeded, but surprisingly rapidly the vast Aral Sea dried up, becoming a literal desert, littered with polluted wreckage of former fishing and other industries and corporations. The post-Soviet countries of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan inherited a deeply scarred landscape.

Their environmental catastrophe has now degraded the economy and the social fabric as well, quality of life has collapsed, and as many as one-third of the population has either left or has become dependent on migrations and remittances from abroad.

This disaster spread across four countries (Tajikstan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakstan and Uzbekistan) and it also literally illustrates the ‘downstream’ effects of these sorts of failures. When we get a global dynamic that fails the three pillars test on that level… we could face a global catastrophe.

The three pillars of sustainability, economic, social, and environmental are all interconnected. They overlap in different ways depending on the situation. Optimizing for a sustainable future means ensuring that these pillars work together in sustainable development meant to create a better environment for everyone.

* Featured image source

Curious to learn more? Follow these links to learn more about The principles of sustainable development and Sustainable Food Systems.