By Clara Calabuig, based on an interview with Dr. Sarah Flavel.

According to Dr. Sarah Flavel, scholar from the Bath Spa University, the environmental problems that we face today can be explained by the Daoist principle of yin-yang, and thus are a result of a loss of balance in the human-nature relationship: “We have gone too far in exploiting the environment, to the extent that if we do not retreat from this path, we will lose balance completely”.

Daoism would point that if we are not at peace with ourselves, we cannot be at peace with what surrounds us. Therefore, achieving environmental balance at the individual level is fundamental. As Flavel states, if we live our lives like rabbit consumers, we cannot relate to the world in a balanced way since all we are doing is taking –“there is no give and take, no back and forth, no reciprocity established between the natural and the human”. On the other hand, as Flavel puts it, there are industrial, commercial and political forces which are true players in the global game to attain this balance of human-nature, and thus the question is established whether individuals can make enough change on their own terms to change the world. Regarding wu-wei, the Daoist principle of actionless action, the belief doesn’t command one to do nothing, but to act producing less of an interfering effect. And today the relationship between humans and nature does not follow this path as we are interfering in the environment in a very obviously aggressive way. How could a preferable human-nature dynamic fit with urban life and appeal to our lifestyle?

One type of living experience of Daoist ecology are the Daoist “nature sanctuaries” in China. The so-called dongtian (‘cave heavens’) or fudi (‘blessed lands’) appeared for the first time in the province of Sichuan, based on the spiritual belief that individual (inner) well-being is conditional to, and interrelated with, environmental (outer) welfare, and thus built by Daoist monks as humble temples using the available resources in the area. Following the Dao De Jing path (“the Earth respects Heaven, Heaven abides by the Dao, and the Dao follows the natural course of everything”), these sanctuaries were established in mountainous sites and remote forests; they were not seeking human alienation, but trying to integrate and equalize human life as another inhabitant of the planet. For more than one thousand years they have considerably succeeded in preserving biodiversity, conserving natural equilibrium, and reducing human footprint to its minimum by plant gathering, land cleaning, forbidding hunting, and by using biofuels and solar-powered lighting. The Qinling Agreement of the Daoist Ecological Protection Network, joined by 120 temples, pledged to protect the environment for a new green revolution. However, its scarce residents put into question the application of this model into larger populated communities and scenarios. Nowadays our economic model and way of living is endangering and is pushing the ecological limits and capacity of the planet; but, is it possible to conceal both alignment with nature and commodity?

Dr. Flavel stresses the view that an urban environment should not be regarded as an unnatural environment. If we started to understand our cities within the broader landscape of nature as a whole, she explains, it could change our present attitude. “Redirecting our relationship with nature doesn’t have to imply that humans become a completely different creature, but that we do need to undergo a process of rebalancing”. In China, the scholar explains, efforts are being made in trying to develop models of eco-cities, creating urban spaces that include nature and thus attempting to remove the dichotomist opposition between the urban and the rural, whilst also minimizing the environmental damage that is generally considered an externality of any populous city. For while we won’t abandon cities, Flavel establishes, this idea of concealing both nature and society is put at the forefront of political thinking in China in trying to maintain a relation with nature that is not exhausting, abusing, and lacking balance. Indeed, the scholar even suggests that we already have this relationship adhered in our livelihoods to some extent: “where there is not access to alive animals in the city, people have pets”. We also acknowledge the appearance of certain establishments destined to this purpose, like thematic coffee shops (i.e. cat cafes), and this incarnates a need to return to a greater contact with nature, even to the “animality” that we have lost.

It is undeniable that Daoist practitioners exhibit a completely different lifestyle –“they don’t eat meat, they usually live in monasteries or temples where they seek to live in tune with living in modesty and nature…”- but in China, the scholar explains, lay people likewise follow Daoist ideas as the Yin-Yang, which has influenced, for example, Chinese traditional medicine enormously, even when it is practiced in tandem with Western medicine. For example: if you are hot you shouldn’t drink cold beverages for it is going to interrupt your balance; heal the body from the outside instead of having surgery; or acknowledge certain illnesses with spiritual and inner imbalance. These beliefs have favoured Chinese people enormously, who have historically shown greater life expectancies. This is now changing due to a developing taste for Western food that contains greater doses of meat, or frequenting fast food chains like McDonalds, which are becoming very popular as well. Originally, Dr. Flavel explains, traditional Chinese diets avoided over-excesses, and it has recognized the importance of movement, lack of stress and psychological and emotional as well as physical well-being. Chinese medicine is holistic and gives great importance to preventive action. All these aspects, as can be noted, descend and are influenced by Daoism.

Xi Jinping’s government, the author explains, has repeatedly stressed their commitment to the promotion of Daoism and Confucianism as to recover Chinese national identity, but also for the positive ultimate impact in ecology it could entail, regarding sustainability in the management of natural resources. It is also noticeable the huge amount of action adjustment behaviour per capita towards the environment that the country is accomplishing, “more than any nation on earth”, and for this reason, Dr. Flavel acknowledges the genuine interest in the party to adjust the degree in which China is playing its part in the environmental conundrum.

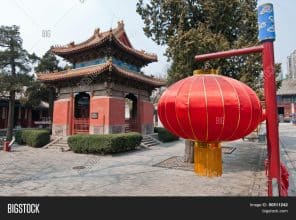

A convinced Daoist practitioner is committing their life to the preservation of local natural environment, with its cycles and in the entirety of the complexity of the surrounding ecosystem. Therefore, should Daoism gain followers, the range of committed guardians of ecological balance of their respective surroundings would concurrently grow. However, relevantly, Flavel concludes, it is worth noting that there are Daoist temples in the centre of Beijing, still preserving a distinctively quiet and reflective environment that emulates nature strategically making use of plants. The Daoists that dwell there eat differently and present a certainly different lifestyle; and thus “they live in kind of sanctuaries within that which is urban”. This, the scholar states, is again proof that Daoism could contribute to the elaboration of the most needed eco-cities, which for their success require not being addressed only from material urbanism, but from the social relations that are expected to develop within.

This interview was conducted by Mariona Bonsfills Clotet in light of the BA in Global Studies dissertation “The Dao in Life on Land: a way to sustainability”. University Pompeu Fabra. Academic year 2018/2019.

More about Dr. Sarah Flavel:

Sarah Flavel is a senior lecturer in Religions, Philosophy and Ethics at Bath Spa University. Her previous research has focused on the Buddhist Kyoto school philosopher Keiji Nishitani through the comparative lens of his critical relationship to the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche. Sarah serves as an editor for Comparative and Continental Philosophy (Taylor and Francis Journals) and is an Associate Board Officer of the Comparative and Continental Philosophy Circle, one of the largest international societies dedicated to the study of global philosophy.